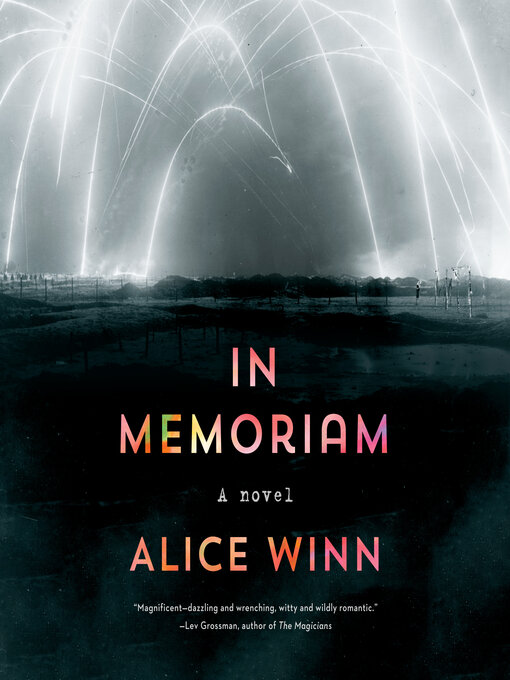

Many reasons have been given for the decline of the climate-change movement in the twenty-first century. I would propose Derangement itself. The planet, with almost 200 jostling nations, was already tense. Some historians have marked the beginning of the new dark age with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and that is where quite a few history books begin or end. I would propose the first climate war in 2036, one in a sequence, between two nuclear states, India and Pakistan, traditional enemies. One issue was water, once plentiful in the form of Himalayan glacier-fed ice-melt. Now, as long predicted, drying up. The two states were prepared to obliterate one another. The world, as the cliché ran, held its breath, and it is not easy to organise or attend mass protests in favour of decarbonising civilisation or write books about it when you are holding your breath.